The goal of this blog post is to explain why modern LLM architectures use SwiGLU as the activation function for the feed-forward part and have moved away from ReLU.

Table of contents

- Q1: Why do we need activation functions at all?

- Q2: What’s wrong with ReLU?

- Q3: What is the Swish activation function?

- Q4: What are Gated Linear Units (GLU)?

- Q5: What is SwiGLU then?

- Final note

Q1: Why do we need activation functions at all?

Consider this: a neural network is essentially a series of matrix multiplications. If we stack linear layers without any activation function:

\[y = W_3(W_2(W_1 x))\]

This simplifies to:

\[y = (W_3 W_2 W_1) x = W_{combined} x\]

No matter how many layers you stack, it’s still just a linear transformation. The network can only learn linear relationships.

Activation functions introduce non-linearity, allowing the network to approximate complex, non-linear functions. This is the foundation of deep learning’s expressive power.

Now, if you have a hard time mentally visualizing the impact of applying activation functions, I highly advise you to watch the section 3 of this video from Alfredo Canziani’s Deep Learning course. It will help you build a great intuition!

Q2: What’s wrong with ReLU?

ReLU literally revolutionized deep learning:

\[\text{ReLU}(x) = \max(0, x)\]

It’s simple, fast, and solves the vanishing gradient problem that is a problem with functions like sigmoid or tanh.

While people usually list problems that might be encountered when ReLU is used like the dying neuron problem, these problems are either theoritical or can be well managed most of the time with techniques used in neural networks nowadays (batch normalization, adaptive learning weights, etc)

Q3: What is the Swish activation function?

Now, before moving to SwiGLU, we’ll look at an activation function Swish that is part of SwiGLU

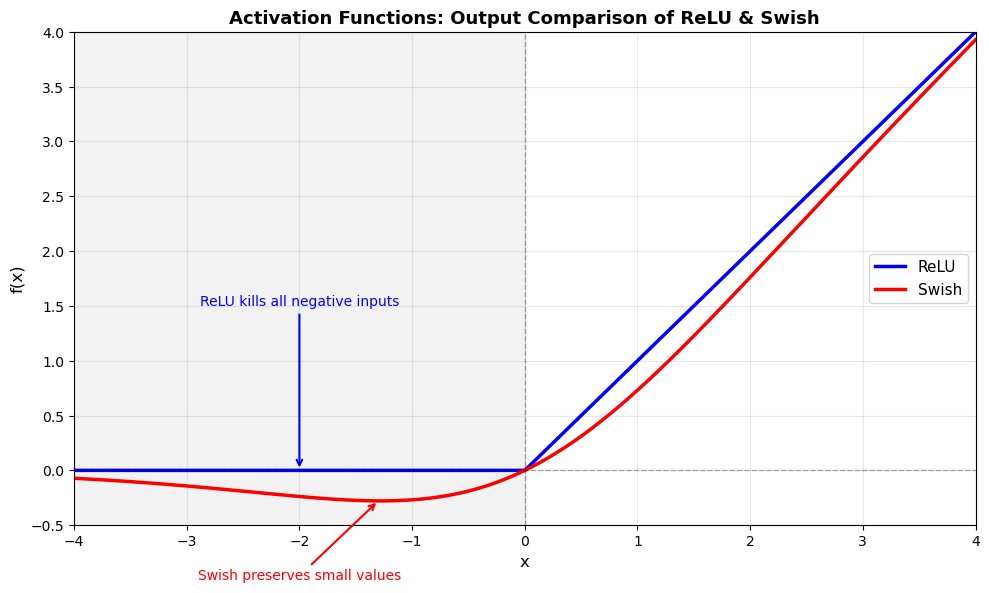

\[\text{Swish}(x) = x \cdot \sigma(x) = \frac{x}{1 + e^{-x}}\]

Swish is a ‘self-gated’ activation function: the input \(x\) is multiplied by its own sigmoid \(\sigma(x)\), which acts as a gate that controls how much of the input passes through.

Looking at how the gate behaves: - When \(x\) is very negative: \(\sigma(x) \approx 0\), so the gate is closed (suppresses the output) - When \(x\) is very positive: \(\sigma(x) \approx 1\), so the gate is fully open (passes the input through almost unchanged)

Despite the bit more complicated formula, Swish has a very similar behavior to ReLU.

Is Swish better than ReLU?

Empirically, Swish is found to work better than ReLU but like many things in deep learning, we don’t know for sure why Swish works better, but here are the key differences:

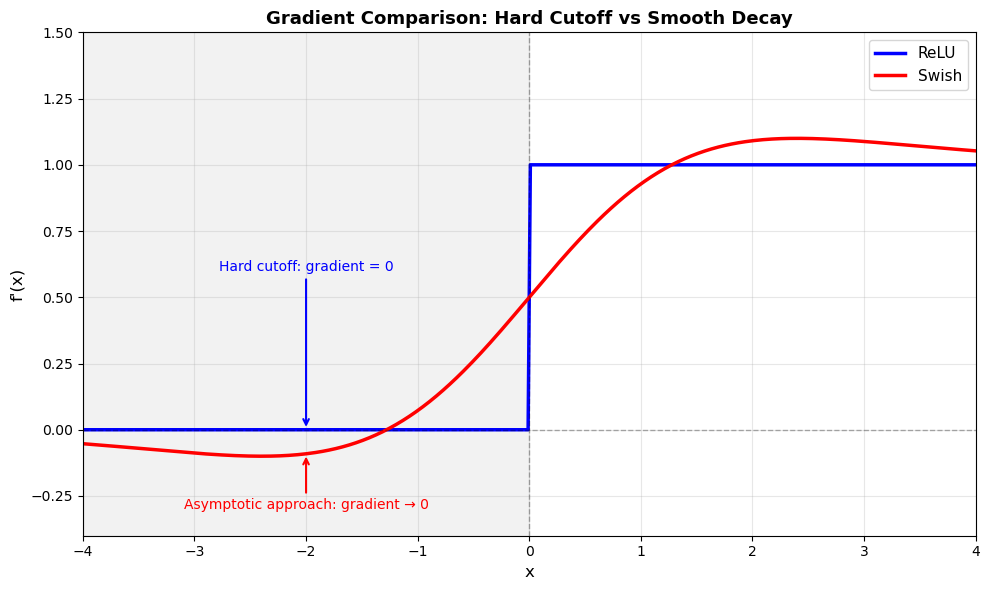

1. No hard gradient cutoff

Looking at the plot above, the key difference is how they handle negative inputs:

- ReLU: Hard cutoff at zero

- When \(x < 0\): output = 0 & gradient = 0 (exactly)

- This is the dying neuron problem (though as mentioned in Q2, it’s often manageable with modern techniques like BatchNorm)

- Swish: Smooth, gradual approach to zero

- For negative \(x\): gradient approaches zero asymptotically but never exactly hits zero for finite values

- Neurons can theoretically always receive updates (though updates may be negligible for very negative inputs)

2. Smoothness

ReLU has a discontinuity at \(x = 0\) (derivative jumps from 0 to 1). Swish is infinitely differentiable everywhere, which means that the gradient landscape is smooth. Whether this smoothness contributes to the performance of Swish is not 100% clear but it’s plausible that this helps with optimization

Q4: What are Gated Linear Units (GLU)?

Now, this is our last component before getting to SwiGLU. Let’s talk about GLU.

\[\text{GLU}(x, W, V, b, c) = (xW + b) \odot \sigma(xV + c)\]

Where: - \(x\) is the input - \(W, V\) are weight matrices - \(b, c\) are bias vectors - \(\odot\) is element-wise multiplication - \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function

The first thing that you should note is that GLU uses a gating mechanism and is somehow similar to Swish in that manner. The difference is that instead of applying the same transformation (identity) to all features and then gating with a fixed function (sigmoid), GLU uses two separate linear projections:

- \(xW + b\): this just takes the input & transforms it. It is usually called the content path

- \(\sigma(xV + c)\): this second part says how much of the content of each feature should pass through and for that, it’s called the gate path

So, GLU can really be thought of as a generalization fo Swish

Why is multiplicative gating powerful?

The element-wise multiplication \(\odot\) allows the gate to select which element of the content to let pass through. The gate can completely suppress certain features (when \(\sigma(xV + c) \approx 0\)) while fully passing through others (when \(\sigma(xV + c) \approx 1\)).

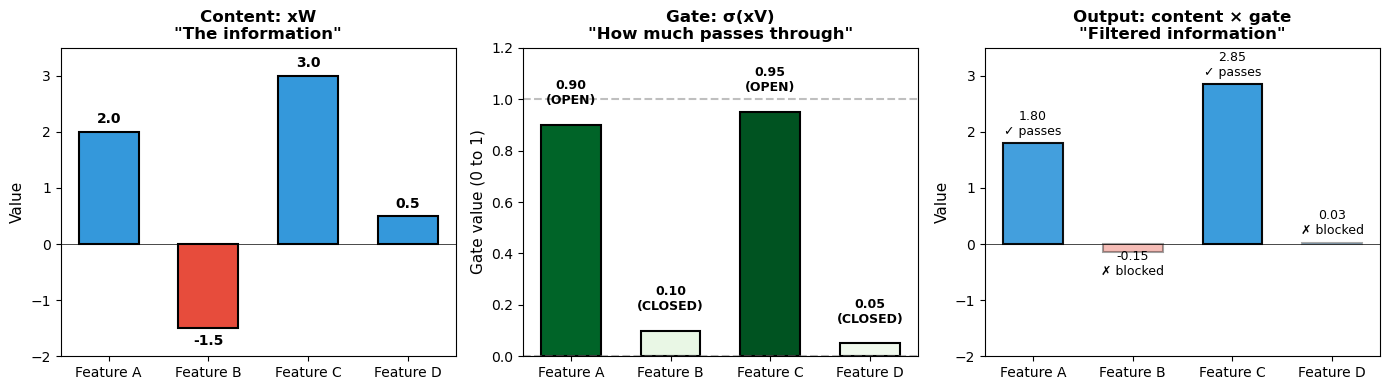

Concrete example of gating

let suppose we have a 4-dim vector \(x\)

\[x = [1.0, -0.5, 2.0, 0.3]\]

GLU applies 2 transformations to this same input:

- A transformation to the content through the content path: \(xW + b\). Let us say that it produces \([2.0, -1.5, 3.0, 0.5]\)

- A 2nd transformation that’s supposed to play the role of the gate: \(\sigma(xV + c)\). Let us say that it produces \([0.9, 0.1, 0.95, 0.05]\)

The GLU output is their element-wise product:

\[\text{GLU output} = [2.0 \times 0.9, \;\; -1.5 \times 0.1, \;\; 3.0 \times 0.95, \;\; 0.5 \times 0.05]\] \[= [1.8, \;\; -0.15, \;\; 2.85, \;\; 0.025]\]

This means that:

- Feature 1: Content is positive (2.0), gate is high (0.9) → passes through strongly (1.8)

- Feature 2: Content is negative (-1.5), gate is low (0.1) → blocked (-0.15)

- Feature 3: Content is positive (3.0), gate is very high (0.95) → fully passes (2.85)

- Feature 4: Content is small (0.5), gate is very low (0.05) → suppressed (0.025)

This allows the network to learn complex decision rules: “for inputs like \(x\), amplify feature 1 and 3, but suppress features 2 and 4.”

Q5: What is SwiGLU then?

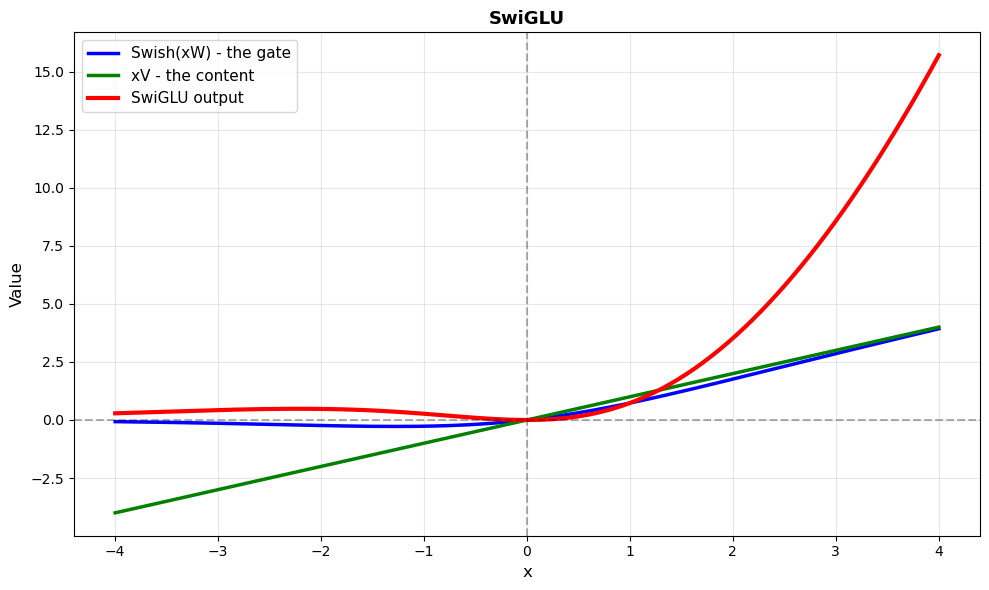

Now we have all the pieces. SwiGLU (Swish-Gated Linear Unit) simply combines Swish and GLU:

\[\text{SwiGLU}(x, W, V) = \text{Swish}(xW) \odot xV\]

That’s it. Instead of using sigmoid for the gate (like in GLU), it uses Swish. That’s why it’s called Swish + GLU.

So what does each part of the formula do ? Well, it’s exactly the same logic as GLU as what changes is just the gating function.

- \(\text{Swish}(xW)\): The gate - decides how much of each feature passes through

- \(xV\): The content - the actual information being transmitted

- \(\odot\): Element-wise multiplication - applies the gate to the content

Why does SwiGLU work so well?

Empirically, SwiGLU outperforms other activation functions in LLMs (even though not sure about VLMs for now). But why? Here’s the intuition:

1. Multiplicative interactions create feature combinations

This is the key insight. Consider what each architecture computes:

Standard FFN (ReLU/GELU): output = activation(xW₁) @ W₂

Each output dimension is a weighted sum of activated features. The activation is applied element-wise, this means that the features don’t interact with each other inside the activation.

SwiGLU FFN: output = (Swish(xW) ⊙ xV) @ W₂

The element-wise multiplication \(\odot\) creates products between the two paths. If we denote \(g = \text{Swish}(xW)\) and \(c = xV\), then output dimension \(i\) before the final projection is \(g_i \times c_i\).

Here’s why this matters: both \(g_i\) and \(c_i\) are linear combinations of input features (before the Swish). Their product contains cross-terms like \(x_j \times x_k\). The network can learn \(W\) and \(V\) such that certain input feature combinations are amplified or suppressed.

This is similar to why attention is powerful. Attention computes \(\text{softmax}(QK^T)V\), where the \(QK^T\) product captures interactions between query and key features. SwiGLU brings a similar multiplicative expressiveness to the FFN.

2. Why not use sigmoid in the gate instead of Swish?

GLU uses sigmoid: \(\sigma(xW) \odot xV\). The problem with the sigmoid is that it saturate saturates. For large positive or negative inputs, \(\sigma(x) \approx 1\) or \(\sigma(x) \approx 0\), and the gradient \(\frac{\partial \sigma}{\partial x} \approx 0\). The gate becomes frozen.

Swish doesn’t saturate for positive inputs, it grows approximately linearly (just like ReLU). This implies that: - Gradients flow better through the gate path - The gate can modulate rather than just switch on/off

3. smoothness

Another thing is that SwiGLU is infinitely differentiable & this smoothness likely helps optimization stability.

Final note

SwiGLU’s power comes from its gating mechanism & multiplicative interactions. By splitting the input into two paths and multiplying them, the network can learn which feature combinations matter (which is quite similar to how attention captures interactions through \(QK^T\)).

Combined with Swish’s non-saturating gradients, this makes SwiGLU particularly effective for large models.